polagram topographies

2016 onwards

The start of an ongoing series of experiments. Writing published on Caught by the River in February 2016.

***

Earlier in the year I bought a 1970s Polaroid camera from a Calder Valley charity shop. Housed in a square leather case lined with red fabric, the ‘Land Camera 1000’ – boxy black and white, with a rainbow stripe – came with four films, each long since expired. The box sat on a bookcase in my fell-top studio for most of the year, picked up and turned over in my hands from time to time, then put back on a high shelf, out of the light. And then, a month or so ago, out of curiosity I loaded a film, its sans serif instructions on heavy, dimpled paper unblemished by the years, warnings in twelve languages protected by an airlock of sealed foil. The whorl and warp of the thin black plastic casing suggested a slow leak of battery fluid; the pooling and seeping of a miniature chemical delta.

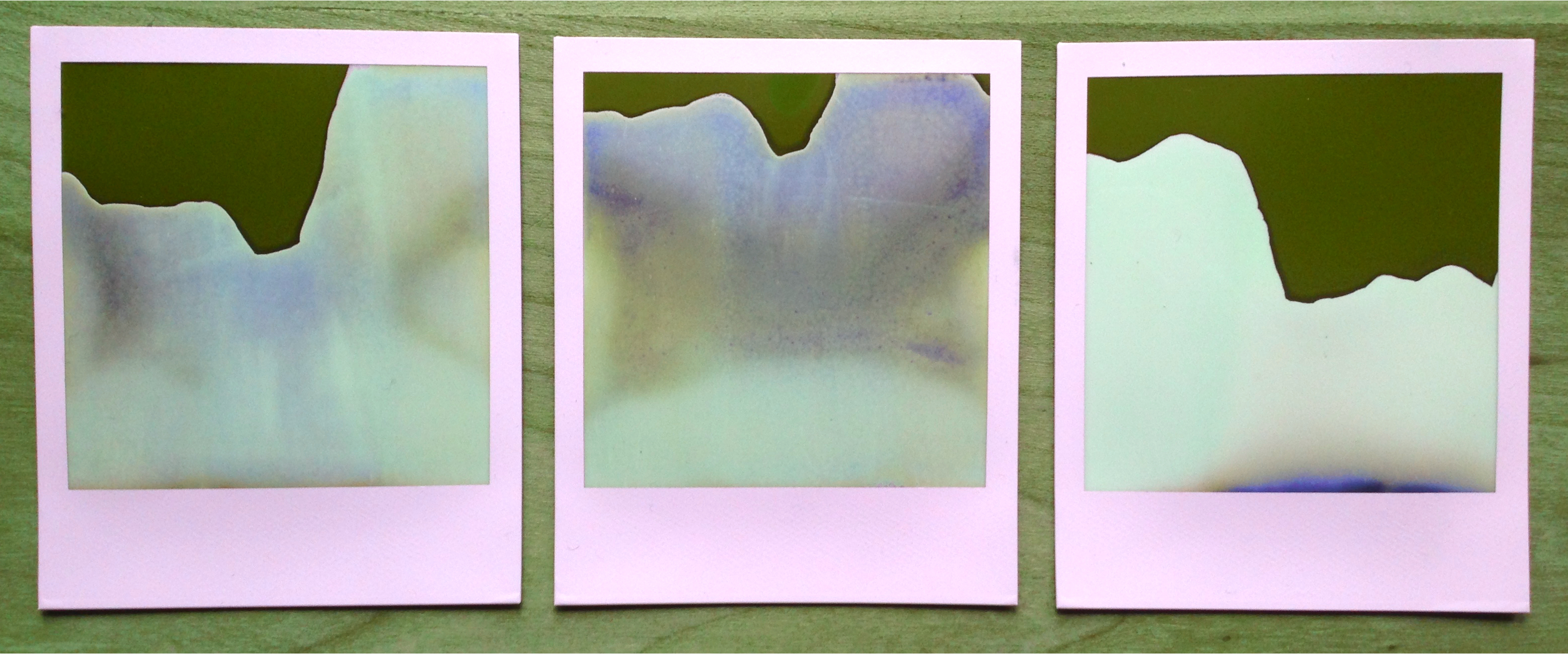

A test shot, framing the dip and uplift of two steep valleys looking south – Staups Moor, Great Rock, Stoodley Pike – emerged with a buzz and flutter, a tear of film and wayward shutter. Torn slightly in the top corner by the camera’s internal mechanisms, the image slowly developed: nothing like the landscape I was looking at, but with a topography of its own. The rips dipped like hanging valleys, the emulsion smudged like sunlight punctuating a day in the clouds. Lined up side by side, new Polaroids taken on walks across the moors seemed to form a mountain ridge, a new ‘landscape’ emergent through unpredictable environmental, chemical and technological processes.

The more I’ve walked the tops and valleys of the Upper Calder Valley, the fewer landscape photographs I’ve taken. The light up here is sometimes scarce yet occasionally overwhelming. Fleeting washes of sunlight illuminate seemingly barren hillsides, picking out gleaming seeps of almost-streams glooping through the peat, or the flash of a grouse breaking cover through burnt-out purple heathers. Yet somehow I’ve been reluctant to take photographs of it all, inhibited in part, I suppose by the hundreds, thousands, millions of photographic landscapes already circling the digital web, usually framing a fixed, super-saturated HDR-sublime of ‘wild’ (or with increasingly othering heights, ‘edgeland’) nature.

In both my writing and art, I’m experimenting ways of thinking about (and through) landscapes in ways that are open and ongoing, that frames the world around us as uncertain, muddled and always in flux, where time has become ever deeper, stranger and hard to pin down. These Polaroids form the beginning of a project experimenting with these ideas called ‘Emergent Landscapes‘. The images themselves change everyday: colours fade, imperfections creep, bubbles emerge as if from some invisible airlocked strata: photographs not of the landscape, yet somehow tied to its forms and fluctuations.